Navigating Speculation and Strategic Realities in India-Pakistan Relations

(06-Jun-2024)

Navigating Speculation and Strategic Realities in India-Pakistan Relations

There is a lot of conjecture on both sides of the Radcliffe Line about the possibility of India and Pakistan resuming their diplomatic relations. Even though the effectiveness of this kind of policy is questionable, recent announcements and events have sparked conversations on the potential for reengagement. Observers have taken particular notice of the Ministry of External Affairs' (MEA) response to former Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's remarks regarding Pakistan breaking the Lahore Declaration by starting the Kargil conflict, implying that communication may resume following India's elections. However, considering both countries' current military and political positions, this optimism could not be warranted.

Relationships with Pakistan: Talking shit or pulling the plug?

Some have read the MEA's recognition of an apparently objective perspective emerging in Pakistan as a sign of a possible breakthrough in relations. This viewpoint has gained popularity, particularly in light of rumors that India may think about reengaging with its neighbor after the election. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, on the other hand, has made it clear time and again that he has no interest in establishing diplomatic ties with Pakistan and that the acts of its neighbor should not impede India's progress. The notion that PM Modi would leave behind mending relations with Pakistan has been emphatically rejected; instead, he has chosen to concentrate on the development of India domestically and its future.

Sometimes, civil servants in Pakistan, such as Nawaz Sharif, say they would like to interact with India. But Pakistan's military, which wields a great deal of influence, continues to act aggressively. Prospects for reengagement are further complicated by recent statements made by Pakistan's Formation Commanders, which not only reaffirmed support for Kashmir's self-determination but also denounced India's treatment of minorities. The ongoing tension is highlighted by Pakistan's constant use of nuclear hyperbole in reaction to the government's denial of their nuclear threats.

Incorrect Optimism

It's unclear what is causing the present confidence for reengagement. Since the terrorist assault in Uri in 2016, the government has adhered to a consistent policy, which has been strengthened by initiatives like the airstrikes in Balakot and the 2019 constitutional amendments in Jammu and Kashmir. This strategy calls for maintaining lines of communication open while putting Pakistan on the back burner. India's determination to take a tough stand has been reinforced by Pakistan's predictable responses to these developments throughout time, which have included downgrading diplomatic relations and suspending trade.

Pakistan may feel compelled to interact with India given the difficulties it faces on its western borders with Iran and Afghanistan and the fact that its relationship with China has not had the intended transformative effect. Pakistan's strategy, however, frequently entails selective engagement, looking for advantages like trade while keeping up its support for terrorism. Reengagement proponents in India contend that Pakistan may have learned from its mistakes and advise India to at least give it a shot. This viewpoint, however, ignores the main problem, which is Pakistan's continued hostility toward India. Resuming in these circumstances carries the risk of going back to unproductive previous behaviors and erasing recent progress.

The Re-engagement Advocacy and Government Policy

The intricate dynamics with Pakistan have been skillfully controlled by the government's policies. This tactic calls for keeping lines of communication open but avoiding more in-depth interaction. Re-engagement proponents contend that recent remarks made by Pakistan, particularly by civilian officials, point to a change in direction. But these words don't come with any concrete steps to back up a real shift in Pakistan's position.

The argument in favor of re-engagement is frequently supported by platitudes stating that interacting with neighbors is inevitable. However, this viewpoint ignores the realities of international affairs. Politicians in India who are thinking about getting back into the game could be more driven by political game plans than a well-thought-out national strategy. The government's strategy has proven effective in regulating Pakistan's reactions to India's internal events, in spite of cries for a change in policy.

Pakistan's Strategy of Two Parallel Tracks

In the event of a reengagement, Pakistan is probably going to take a dual, simultaneous strategy. This plan would be to hold negotiations and resume trade while keeping the level of terrorism simmering. The jihad infrastructure would remain operational due to low-intensity strikes. In addition to focusing on Kashmir, Pakistan's plan also aims to weaken Punjab by endorsing Khalistani factions. This dual strategy is demonstrated by the Jamaat Islami's recent political actions in Jammu and Kashmir, where they try to blend in with the political system while separating themselves from terrorism when confronted with scrutiny.

Under this two-pronged strategy, Pakistani civilian authorities may put on a front of cooperation while the military sticks to its guns. This strategy makes use of the myth that helping civilians is essential to stopping military instability. Indian leaders could fall for this ruse, potentially jeopardizing national policy, as they are swayed by Pakistani proponents in India. Furthermore, dealing with Pakistan's weak and powerless civilian administration carries a high risk and little return in terms of strategy.

"Mother India" Complex Redesign?

Some use the "Mother India" concept to claim that normalization with India is necessary in light of Pakistan's current problems. According to this viewpoint, Pakistan might stabilize with India's assistance. This claim, however, is unsupported by facts and ignores Pakistan's ongoing animosity. The Pakistan Army's resistance to creating a new front is not indicative of a sincere wish for peace. Actions like halting incitement in Punjab, ending support for terrorism in Kashmir, and addressing the presence of internationally recognized terrorists within Pakistan would be real signs of reform.

There is little reason to think that there would be a real change towards peace unless Pakistan takes decisive measures. The current approach, which has proven effective over time, must be maintained by the incoming Indian administration. Modifying this strategy at this point runs the danger of undoing major progress. India should have a pragmatic approach to Pakistan; it should not be influenced by sentimental or wistful thoughts. It has to deal with Pakistan as an adversarial state as well as the poisonous ideology that drives its behavior.

In summary

India's approach to Pakistan has been successful in managing a complicated and frequently antagonistic relationship. Conjecture over a possible reunion, stimulated by recent pronouncements and events, ignores the underlying problems that still exist. Trade and conversation may appear desirable, but they run the risk of returning to outdated, inefficient practices. It is important to proceed cautiously with any reengagement to prevent unduly undermining the noteworthy advancements achieved in the last few years. India's strategic interests and security depend on an emotionless, practical policy that tackles Pakistan's state and mentality.

Reviving Africa's SDGs: The Need for Global South Partnerships and Financial Reforms

(06-Jun-2024)

Reviving Africa's SDGs: The Need for Global South Partnerships and Financial Reforms

A significant amount of funding is needed to revitalize Africa's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the existing global financial system is not providing it. To address this issue, the African Union (AU) needs to step up its efforts and establish alliances with nations in the Global South. Following two decades of economic growth, Africa is currently confronted with formidable obstacles, such as food shortages and debt, which are made worse by the COVID-19 epidemic and the confrontation between Russia and Ukraine. The AU's financial reform leadership is essential to realigning Africa's SDGs.

Historical Background and Present-Day Difficulties

Sub-Saharan Africa saw strong economic growth between 2000 and 2010, averaging 5 percent yearly, and notable progress was made in terms of development. From 56% in 2000 to 42.1% in 2010, poverty rates decreased. But this progress was severely hampered by the COVID-19 epidemic, and the ensuing war between Russia and Ukraine led to a terrible food shortage that affected the entire continent. More than half of Africa's low-income nations are in economic trouble as a result of the region's ongoing catastrophic debt crisis. Ethiopia, Zambia, Ghana, and Mali have already fallen behind. About 39 million Africans lived in extreme poverty in 2021, and millions more experienced severe food insecurity. Approximately 33 African countries also needed outside food aid.

Africa's SDG progress is still unequal and sluggish. In the absence of swift action and a significant financial infusion, accomplishing the SDGs will prove to be an elusive objective. Since the SDGs were adopted in 2015, financing has been a major obstacle to their implementation. The 2030 Agenda placed a strong emphasis on satisfying aid pledges, utilizing private sector funding, and bolstering domestic resource mobilization in addition to creative finance methods. Nonetheless, the majority of emerging African nations find it extremely difficult to raise domestic funds through taxes.

Financial Difficulties in Implementing the SDGs

Africa is estimated by the UN to face a crippling annual SDG financing gap of over $200 billion. Increased debt loads, expensive borrowing, and constrained budgetary resources make this problem even worse. By 2023, the average Sub-Saharan African nation was paying almost 12 percent of its income on interest payments, severely limiting development investment. The public debt to GDP ratio had reached its peak at 60 percent. The investment climate in Africa has been disproportionately impacted by global crises. Following the epidemic, high-income nations witnessed the largest-ever share of greenfield foreign direct investment (FDI) at 61 percent, while Africa's contribution fell to 6 percent, the lowest level in 17 years. Africa's high cost of financing makes investments in important industries like renewable energy difficult.

There is also a decrease in traditional economic sources like official development assistance (ODA). Aid to poor nations decreased by 2% after the pandemic, despite record ODA levels, as a result of resources being diverted to host refugees in donor nations following the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. At 3.5 percent, the fall was much more noticeable for Africa. Developed nations have also fallen short of their commitment, made at the Copenhagen Climate Summit, to provide $100 billion in climate funding yearly by 2020. Africa may experience another "lost decade" if the SDG agenda is not significantly bolstered by outside assistance.

Systemic Financial Reforms Are Necessary

Even though ODA is still important, it is insufficient on its own. Africa's interests are not served by the international financial architecture, and deeper systemic reforms are required in order to mobilize resources to finance the SDGs throughout the continent. With the industrialized North able to offer significant economic stimulus and receiving the majority of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the epidemic brought attention to the gap between the North and the South. In contrast, fiscal space was scarce in African nations, where the average stimulus package amounted to a mere 1.5 percent of GDP. Just 3% of the SDRs provided by the IMF went to African countries.

The mounting evidence of Africa's underrepresentation in international financial institutions has prompted calls for revamping the global financial order. Africa's economic advancement is impeded by inherent biases in tax laws, loan contracts, economic conditionalities, credit ratings, SDR distribution, and restricted participation and voting rights in international bodies. The permanent membership of the African Union (AU) in the G20 was a symbolic move that gave a continent that had been traditionally excluded on international platforms representation. But rather than just following the rules, Africa needs to take use of this chance to promote equal participation, economic justice, and financial reforms.

The Strategic Goals and Projects of AU

Africa presented a number of demands for a global financial system that supports its interests during the AU Summit in February 2024. The debt problem must be resolved, more grant and concessional monies must be obtained, SDRs must be redirected to African financial institutions, African representation and decision-making authority must be increased in international organizations, and an industrialization program centered on green growth must be committed to. In order to improve cooperation and address Africa's funding issues, African Multilateral Financial Institutions (AFMIs), including the African Export-Import Bank and African Finance Corporation, established the "Africa Club," or Alliance of African Multilateral Financial Institutions.

While the AU's activities are significant, forming alliances with nations in the Global South is just as vital. The AU's admission to the G20 is appropriate given that South Africa, Brazil, and India are the ones that set the G20's agenda. India in particular has been a steadfast ally, speaking for the Global South and pushing for AU's permanent G20 participation. Africa will benefit from close ties with these nations, which will strengthen its position and promote systemic financial reforms.

In summary

In summary, significant funding is needed to realign Africa's SDGs and stop another "lost decade" for the continent. Deep structural changes are required because the current global financial system is insufficient. To further its goals, the AU has to be more aggressive in promoting these reforms and forming strong alliances with nations in the Global South. The effective mobilization of resources and the creation of a more just international financial system are critical to Africa's prosperity in the future.

Increasing Maritime Connectivity: The Direct Shipping Link between Chattogram and Ranong

(06-Jun-2024)

Increasing Maritime Connectivity: The Direct Shipping Link between Chattogram and Ranong

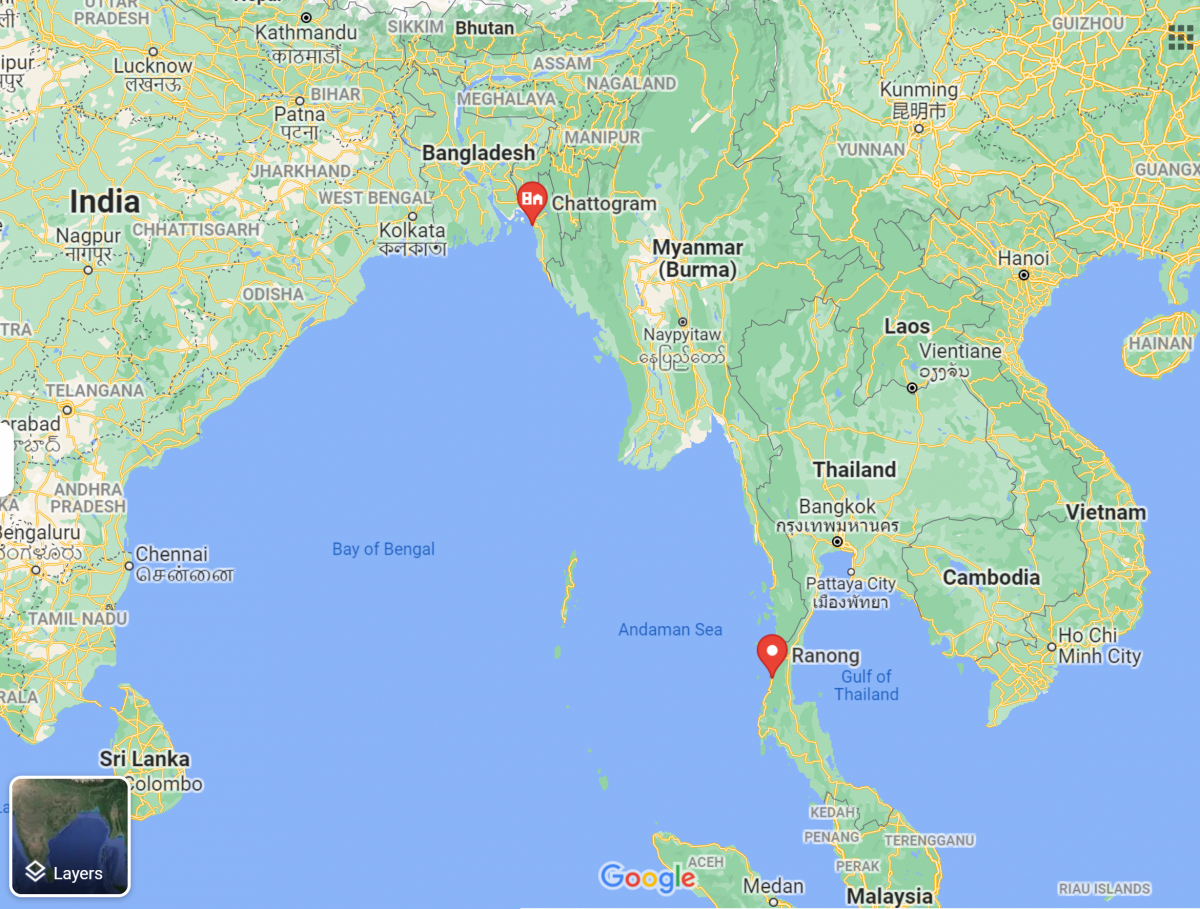

With a shared marine area, the Bay of Bengal offers Bangladesh and Thailand a special chance to expand their bilateral trade. The idea of a Chattogram-Ranong link, which would allow for direct shipping, might be very beneficial to both countries' economies. Bangladesh's and Thailand's coastal regions make effective port connectivity essential for economic expansion. Thailand, on the eastern shore of the Andaman Sea, and Bangladesh, to the north of the Bay of Bengal, might benefit from each other's marine locations. Building on an MoU signed in December 2021, recent talks held during Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's visit to Bangkok have revitalized the notion of developing a direct shipping route between Chattogram Port in Bangladesh and Ranong Port in Thailand.

Improving Port Accessibility

With over 90% of Bangladesh's marine traffic handled by Chattogram Port, the country's main maritime gateway is situated in the southeast of the nation. It is the busiest port in the Bay of Bengal and an important global player, ranking in the top 100 ports in the world according to Lloyd's, hence it is vital to the trade of the area. Thailand's nautical reach is increased by its lone port on the Andaman Sea, Ranong Port, which links to the Bay of Bengal. In an effort to strengthen ties with the Bay's littoral regions, particularly with India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Thailand is actively promoting Ranong.

Bangladeshi exports to Thailand are currently transshipped via Singapore, Port Kelang in Malaysia, and Colombo Port in Sri Lanka, which takes about ten days. The establishment of a direct shipping link would result in a three-day transit time and a thirty percent reduction in shipping costs. Local private enterprises that operate bulk carriers and container ships with a 7-meter draft and a capacity of 10,000 tonnes, or units comparable to 20 feet, might effectively service this route.

Benefits of Shipment Direct

The construction of a direct maritime route between Chattogram and Ranong is expected to increase traveler traffic and trade between Thailand and Bangladesh. A letter of intent to start discussions for a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) was signed during Prime Minister Hasina's visit, with the goal of closing the current trade gap. Bangladesh's exports to Thailand totaled $83 million in 2022, while the country's imports came to $1.17 billion. Increased business exchange and a reduction in trade disparities would be made possible by an FTA.

Furthermore, the direct shipping route would eventually be able to accommodate passenger services, which would be advantageous for the tourism industry—a major area of mutual collaboration between the two nations. 140,000 Bangladeshis traveled to Thailand in 2019—4,300 of them were medical tourists—making it a popular destination for both leisure and business travel. The Thai economy benefited by about $182 million from this migration. PM Hasina signed three memorandums of understanding (MoUs) to improve tourism, waive visa requirements for official passport holders, and cooperate with customs. Future travel campaigns, like those highlighting the Buddhist circuit, may boost traveler exchanges even more.

Advantages in Strategy

The Chattogram-Ranong shipping link benefits both countries strategically in addition to trade and tourism. Thailand benefits from increased trade prospects with the hinterland of Chattogram Port, which includes Nepal, Bhutan, and Northeast India. Bangladesh considers this relationship to be vital and is keen to fortify its links with Southeast Asia. It is imperative that Thailand back Bangladesh's application to become a member of the Mekong-Ganga Cooperation Forum and to be granted ASEAN Sectoral Partnership status in order to address regional problems like the Rohingya crisis.

Through Thailand's Landbridge project, which connects the Andaman Sea with the Gulf of Thailand by roads and railroads, Bangladesh may also have access to the Pacific Ocean through direct shipping. Moving products and people between the Pacific and Indian oceans is made easier by this corridor, which eliminates the need to cross the crowded Strait of Malacca. The Landbridge, if operationalized, will augment the Chattogram-Ranong link and greatly increase commerce in the Bay of Bengal. In line with this initiative, the BIMSTEC Master Plan on Connectivity (2022) calls for the establishment of direct maritime ties between the ports of Chennai and Colombo and Thailand's Ranong Port.

Cautionary Notes in Diplomacy

The direct shipping route has numerous advantages, but there are diplomatic obstacles to its adoption. One major obstacle is the political unrest in Myanmar, particularly in the coastal province of Rakhine, which is located halfway between Chattogram and Ranong. Since talks over the project started in 2016, ongoing tensions between ethnic communities and the military Junta have caused delays. In order to resolve these problems and restore the shipping link, diplomatic measures will be essential.

Another element of difficulty is added by China's growing presence in the Bay of Bengal. There are notable Chinese investments in Bangladesh as well as interest in the Thai Landbridge project, which might serve as a bridge over the Malacca Strait. In keeping with China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank indicated interest in building the Landbridge in February 2024. Bangladesh and Thailand are parties to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and one important aspect of this project may be the direct shipping line between Chattogram and Ranong. Given China's growing influence in the Indo-Pacific area, this possibility may worry India and other countries in the region. Bangladesh and Thailand's diplomatic skills will be put to the test when juggling their economic goals with diplomatic sensitivities.

In summary

Bangladesh's goal is to become a middle-income country by 2031, out of Least Developed Country (LDC) category by 2026, and the Chattogram-Ranong maritime link has significant commercial significance in this regard. This route gives Thailand the chance to expand its trade beyond China and fortify its connections with South Asia. Integrating the maritime link into the Bay of Bengal's regional commerce network while striking a balance between diplomatic and economic objectives is essential to its success. Bangladesh and Thailand can fully utilize their shared maritime area to promote economic growth and regional cooperation by resolving these challenges.